On the final evening of its first week open to the public, the Amazon Go store still drew lines of eager customers. The lines were staffed by employees in orange parkas, who cheerfully engaged with shoppers and handed out high-quality, reusable bags. And the wait was short: no more than five minutes in the Seattle drizzle.

On the final evening of its first week open to the public, the Amazon Go store still drew lines of eager customers. The lines were staffed by employees in orange parkas, who cheerfully engaged with shoppers and handed out high-quality, reusable bags. And the wait was short: no more than five minutes in the Seattle drizzle.

As a frequent Amazon shopper, I experienced a kind of brand disconnect when physically confronted with Amazon mark on something the size of a convenience store. Living in New York City without a car, I use the Amazon apps on my phone far more frequently than I ever drove to the grocery or hardware store back in Massachusetts. While Amazon apps give me a wide selection from workout gear to floor lamps, the physical Amazon Go store was aimed at grab-and-go behaviors: quick snacks, prepared foods, and even a mini liquor store. It also took a moment to re-frame the experience in my head: In this physical Amazon store, the stock is limited, and can actually run out.

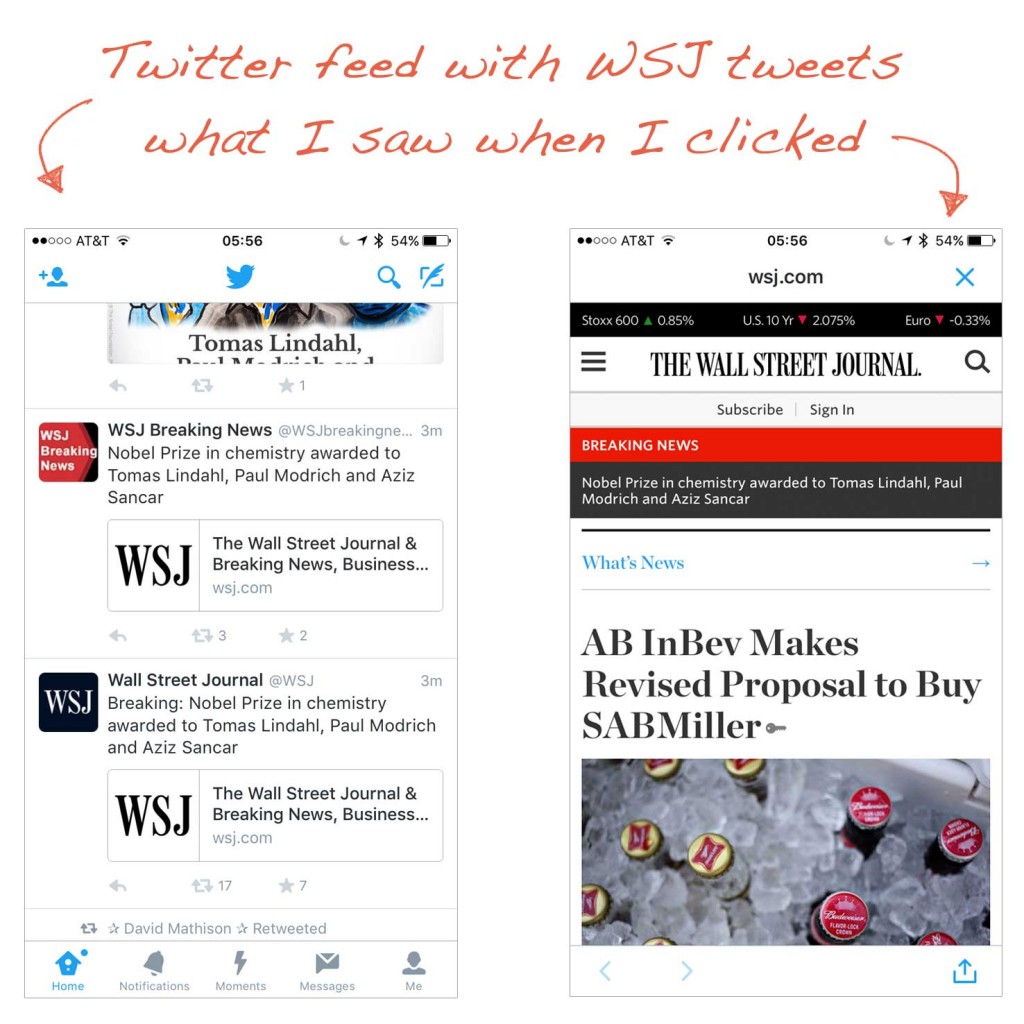

The main event, then, is not the stock selection but the technology. Entry is easy: Anyone who has scanned a mobile boarding pass in an airport would find the turnstiles familiar. In the store itself, there is nothing to scan or interact with to check price or, of course, check out. This is a sharp contrast to the typical, painful automated checkout experience, where there is usually an exhausted staff member assisting the general public in completing each “self checkout” transaction. At Amazon Go the cameras above, and there look to be thousands, are doing the counting for you. And when you leave, you walk out — a behavior some find unsettling, but that I believe will be as easy to adopt as a one-click purchase on an app.

And the technology is breathtaking: I purposefully picked up and replaced more than 10 other items, to see if one would be mistakenly added to my cart, but it was impossible to fool the system. I overheard some shoppers saying that the checkout had experienced issues earlier with the “cameras having trouble reading body type” and charging to the wrong person, but saw no evidence of this. Looking up was instructive: seeing those cameras was a reminder that some of us have walked willingly into the panopticon, trading privacy for seamless commerce. This feels also like a first step: the technology has removed the weight of the interaction and will soon deliver more intelligence about our products and their provenance.

And what of the people? There were several staff at the front, assisting the very occasional shopper who still needed to download the Amazon Go app or had trouble scanning the barcode to get in. There were two people intermittently re-stocking or adjusting product, another back in an employees-only area, and a rather gruff man checking ID in the mini-liquor aisle. The employees were largely friendly, and checked in frequently with shoppers to see if assistance was needed. Oddly, when I asked one what he did he replied, rather ominously, that he could not disclose what his role was. Note to Amazon comms team: “customer support” is a broad and useful catch-all phrase.

How will all this work out for Amazon? Ben Thompson makes a compelling case for Amazon’s thus far successful strategy of pursuing both a vertical and horizontal model. What it means for other kinds of transactions beyond in-store purchase is perhaps more exciting. If a technology can allow you to know the people in your physical space, be it a sporting event or a concert venue, and eliminate bottlenecks, the potential for improving audience experience is enormous.

Originally published on Medium.